Introduction

In 2025, Japanese accounting standards concerning goodwill are approaching a major turning point. The Japanese government’s Council for Promotion of Regulatory Reform has compiled a report, including recommendations to abolish the mandatory periodic amortization of goodwill under traditional Japanese GAAP or to transition to an elective system of non-amortization or amortization. The Council plans to request that the Accounting Standards Board of Japan (ASBJ) consider these changes.

This move aims to promote M&A involving startups, thereby fostering corporate revitalization and strengthening international competitiveness. However, the non-amortization model also presents significant risks and challenges.

In this article, we will delve into the background of this systemic change in goodwill accounting, the practical challenges, and its relationship with international trends, incorporating examples from Europe and the United States.

Challenges Posed by the Japanese Amortization Model

Under Japanese accounting standards, goodwill recognized in M&A has been required, as a general rule, to be amortized using the straight-line method over a period not exceeding 20 years, with the expense recorded as SG&A (Selling, General and Administrative) expenses each period. This is based on the view that goodwill is an intangible asset whose value diminishes over time.

However, this amortization model has increasingly come to be seen as a systemic hindrance by companies acquiring startups and by venture investors. This is particularly true for startups, which often have low net assets and are acquired based on expectations of future synergies, leading to a relatively large amount of goodwill. The resulting annual amortization expense significantly suppresses profits. This created a phenomenon where the growth potential of the acquired company was not easily reflected in the financial statements, making the M&A appear “unprofitable.”

Furthermore, IFRS (International Financial Reporting Standards) and US GAAP treat goodwill as non-amortized, meaning periodic amortization is not performed. This discrepancy has complicated international accounting comparisons and has been a factor disadvantaging Japanese companies in global M&A competition.

Against the backdrop of these practical inconveniences and the handicap in international comparisons, the government has pivoted toward introducing an impairment-only model for goodwill accounting, aligning with international standards.

Expectations for the Impairment Model and Its Reality

The transition to an “impairment-only model,” where goodwill is not amortized, appears on the surface to be a logical systemic change. This is because it is based on the concept that goodwill reflects the future expectations inherent in a corporate acquisition and should not be expensed unless its value has been impaired.

If non-amortization is adopted, companies can make financial projections without considering amortization expenses, facilitating acquisition decisions. Moreover, as the treatment aligns with IFRS and US GAAP, it simplifies international performance comparisons and makes it easier to gain the understanding of foreign investors.

However, this impairment model presents many practical challenges.

The first issue is the “postponement of impairment.” In Europe and the United States, there have been many cases where, several years after an acquisition, goodwill remained on the books even though the business had effectively failed to produce results. Companies would only recognize a massive impairment loss at the end of a fiscal period, long after acknowledging performance deterioration. This is the phenomenon known as “Too little, too late.”

For example, when Kraft Heinz announced a staggering $15.4 billion impairment in 2019, causing its stock price to plummet, and when Sequential Brands suddenly announced a goodwill impairment exceeding $300 million in 2017, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) questioned the adequacy of their disclosures.

Additionally, impairment testing is an extremely complex and costly process, involving the identification of CGUs (Cash-Generating Units), forecasting future cash flows, and measuring fair value. The burden of implementation is particularly heavy for SMEs and startups, which risks causing systemic fatigue.

Global Trends and the Re-evaluation of Amortization

As the limitations of the impairment-only model have become apparent, the significance of the amortization model is being re-evaluated globally. In a Discussion Paper issued by the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) in 2020, many stakeholders responded positively to the question of whether the reintroduction of goodwill amortization should be considered.

Furthermore, the FASB (Financial Accounting Standards Board), which sets US GAAP, introduced a simplified accounting alternative for private companies in 2014, permitting the amortization of goodwill over a maximum of 10 years. Under this model, impairment testing is required only when a triggering event occurs, achieving both a reduction in the operational burden and an improvement in the predictability of expense recognition.

In Europe, EFRAG (European Financial Reporting Advisory Group) and other bodies have proposed a return to a “hybrid model of amortization plus impairment,” and understanding among investors is growing.

Against this backdrop, it is considered highly likely that Japan will also move toward designing a hybrid system that combines impairment with amortization under certain conditions, rather than simply adopting the non-amortization model.

Conclusion

The accounting treatment of goodwill is a theme deeply intertwined with a company’s acquisition strategy, capital policy, and even its dialogue with investors. What is required is not merely aligning the system with IFRS, but enhancing transparency in a manner suited to the practices of Japanese companies, while simultaneously ensuring international consistency.

The introduction of the non-amortization model necessitates improvements in governance, such as the early recognition of impairment factors, stricter testing, and expanded information disclosure. At the same time, companies themselves must adopt a perspective that considers how their accounting policies will be perceived by investors and the market.

The reform of goodwill accounting is a critical issue directly linked to the future growth and market valuation of Japanese companies. Now is the time for a return to the essence of financial reporting, striving for information that is “understandable, comparable, and reliable.”

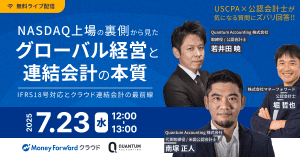

Our firm provides support for Japanese companies listing on Nasdaq, as well as assistance with all other cross-border transactions. If this article has piqued your interest and you wish to learn more, please do not hesitate to contact us. We look forward to the opportunity to speak with you—those who are driving forward today with an eye toward the future—and to offer our support. We will also endeavor to provide synergistic human connections. Please feel free to reach out to us using the inquiry form below.